The Collision of Faith and Public Education

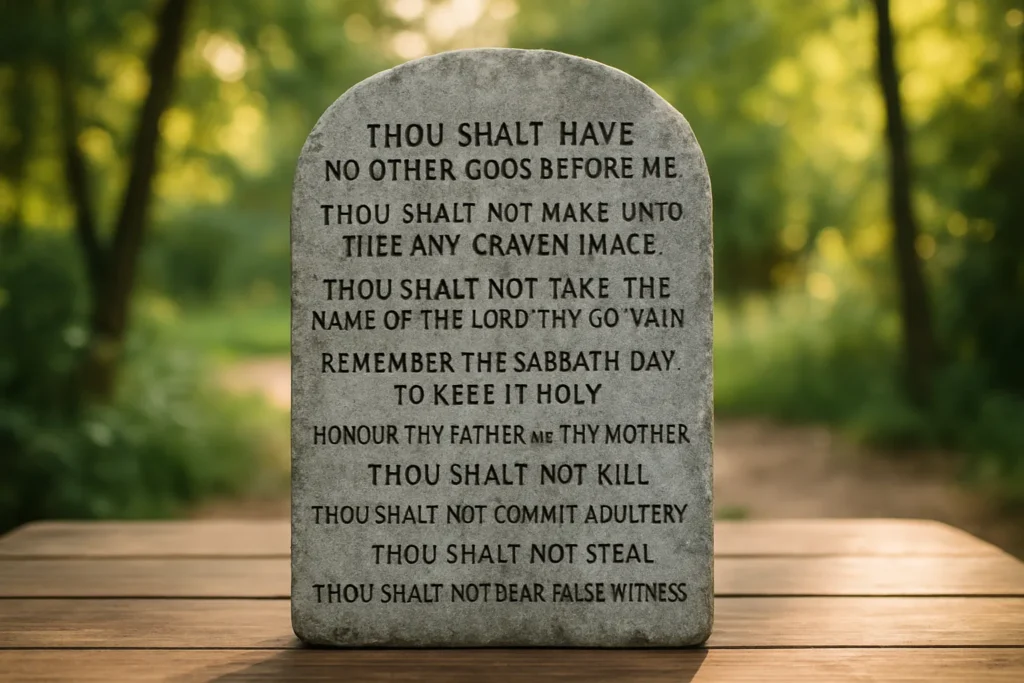

Imagine stepping into your child’s public school classroom and spotting a large, government-mandated display of the Ten Commandments. For many Arkansas families, this scenario is about to become reality following the passage of Act 573 of 2025: a law requiring public schools to display the Ten Commandments and the phrase “In God We Trust” in every classroom and library. The imagery is unmistakably bold, but the implications run deeper—a collision of faith, freedom, and schooling that’s now at the center of a major federal lawsuit.

Seven families from a spectrum of backgrounds—Jewish, Unitarian Universalist, atheist, agnostic, Humanist, and a former Mormon—have brought a federal challenge against Act 573, arguing it violates their children’s First Amendment rights and undermines the core promise of American religious liberty. Their lawsuit, Stinson v. Fayetteville School District No. 1, now pending in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas, seeks nothing less than to overturn a law they frame as religious coercion clothed in patriotic intent.

The law’s requirements are strikingly specific. Not only must every public classroom and library display the Ten Commandments—at least 16 by 20 inches, clearly visible—but each display must use a particular, unnumbered paraphrase of the King James Version, a translation historically associated with Protestant Christianity. In an attempt to sidestep legal precedent, Arkansas lawmakers stipulated that displays must be paid for with private donations. This technicality, however, does little to mask the fact that state law is compelling the presence of religious doctrine in secular, taxpayer-funded spaces.

Parents involved in the lawsuit span four northwest Arkansas districts: Fayetteville, Springdale, Bentonville, and Siloam Springs. For them, the law is not just a hypothetical concern. It’s a direct affront to their families’ beliefs and to their constitutional right to raise their children with—or without—a particular set of religious teachings.

Legal Precedent, Parental Rights, and Historical Lessons

What’s at stake? At the heart of this battle is the First Amendment—a guarantee that government will neither establish nor prohibit the free exercise of religion. As the Supreme Court declared more than four decades ago in Stone v. Graham, a similar Kentucky law mandating the posting of the Ten Commandments in classrooms was struck down because its “pre-eminent purpose [was] plainly religious in nature.” The Arkansas law’s nearly identical requirements and language make its legal prospects murky at best.

Supporters, like Rep. Jeremy Woolridge—who openly declared his motivation to “spread that gospel” in legislative debate—argue the law simply restores a moral foundation to public life. But critics counter that such proclamations reveal an explicit religious agenda incompatible with public education’s pluralistic mission. In his coverage, University of Arkansas law professor Steve Sheppard notes that “simply citing moral values doesn’t make a law secular in effect, especially when it is tied to one specific religious tradition.”

The display of the Ten Commandments was once common in American schools—until the Supreme Court’s decisions in the 1960s and 1980s established clear lines between church and state. Since then, cases like these have tested those boundaries repeatedly, often with profound ripple effects for civic unity and individual freedoms. The reality is that requiring all students to face a singular, state-approved version of religious doctrine tilts public education away from inclusion and toward exclusion.

The Arkansas case is not in a vacuum. Earlier this year, Louisiana passed a similar mandate, and Texas lawmakers are pursuing their own. But history shows that such attempts to infuse classrooms with religious symbols rarely stand up to constitutional scrutiny—the Fifth Circuit, for example, was unambiguous when it blocked Alabama’s effort to require school prayer and religious mottos. Even some religious leaders, including prominent Baptist organizations, have joined the opposition. Their argument? True faith does not require government sponsorship; it flourishes in the freedom of the individual conscience.

“When the state picks a religious script—no matter how familiar—it sends a message to every child who does not share that belief: You are an outsider in your own public school.”

A closer look reveals a deeper constitutional issue: parental rights. According to the lawsuit, parents—not lawmakers—have the right to direct their children’s religious and moral upbringing. For the Jewish and Unitarian Universalist families involved, the law’s narrow reading of religion directly conflicts with their own traditions of interpretation, dissent, and inclusion. As Harvard constitutional scholar Laurence Tribe recently stated, the First Amendment “exists to protect not just majorities, but minorities—including religious minorities—from enforced conformity.”

The High Cost of Exclusion and Division

How does this controversy affect real children? According to testimony from families in the lawsuit, students from non-Christian backgrounds already feel pressure to downplay their identities in environments dominated by majority faith traditions. Adding mandatory displays of specifically Christian scripture risks deepening feelings of alienation—and invites subtle, pervasive forms of peer and teacher pressure.

Polls show Arkansans are deeply religious, but attitudes toward government-imposed religious observance differ sharply by generation and faith background. According to a recent Pew Research study, a majority of Americans—including many Christians—say public schools should remain religiously neutral. As Unitarian Universalist parent Sarah Feldman told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, “We teach our children to think for themselves. When the government tells them what to believe, it undermines trust in both church and state.”

The legal battle now underway in Arkansas is more than just a theoretical dispute. It’s about ensuring schools remain places of belonging for every child—Christian, Jewish, atheist, Muslim, or otherwise. Laws that favor one tradition unavoidably send a message that some are less welcome than others. The lawsuit’s plaintiffs are asking the court not only to block the law, but to affirm the nation’s commitment to true religious freedom: a system where faith is a personal choice, not a public mandate.

Arkansas’ law, like similar efforts elsewhere, asks us to consider: Are we willing to trade the constitutional promise of liberty and equality for the illusion of moral conformity? As this case moves forward, it will test whether we truly value a pluralistic democracy—or whether, in the name of faith, we will endorse exclusion over empathy.